The Transatlantic Slave Trade and Ghana: A History of the Gold Coast

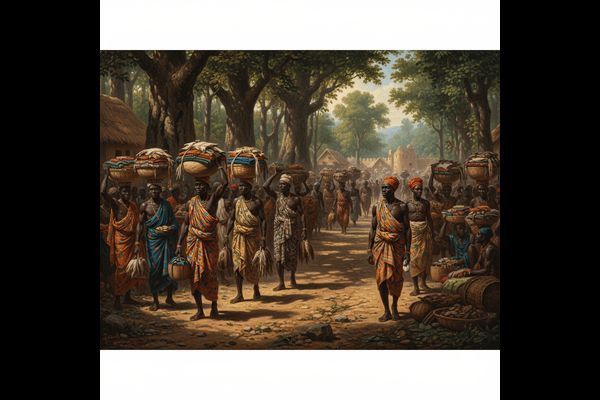

The territory now known as Ghana, historically referred to as the Gold Coast, occupies a unique and tragic place in the history of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. It served as the central hub of European commerce in West Africa for over three centuries, exporting gold, timber, and, most devastatingly, human beings. The remnants of this era—the imposing coastal forts and castles—stand today as stark monuments to one of history's greatest crimes against humanity. To understand the slave trade in Ghana is to trace the profound and lasting impact of global commerce on local societies, demographic patterns, and the collective memory of an entire continent.

I. Early Forms of Servitude and Exchange

It is crucial to preface the history of the Transatlantic Slave Trade with an acknowledgment of pre-existing systems of servitude and regional exchange in West Africa.

Servitude in Pre-Colonial West Africa

Before the arrival of Europeans, various forms of bondage existed in the region. These systems were distinct from the chattel slavery that developed in the Americas:

-

A form of Indentured Servitude: Individuals typically became unfree due to debt, judicial punishment, or being captured in local wars.

-

Social Integration: Often, the offspring of people in servitude could achieve freedom and integration into the host family or clan over generations.

-

No Property Status: Crucially, enslaved people were generally not viewed purely as transferable, sub-human property; their status was often tied to relationships and political power within the community.

The Trans-Saharan Trade

The primary external trade route involving human bondage was the Trans-Saharan slave trade. Dating back over a millennium, this route moved enslaved people from West African interiors north across the Sahara to North Africa, the Middle East, and Mediterranean Europe. This established a network and precedent for the movement of people for commercial purposes, which the Europeans would later tap into.

II. The Arrival of Europeans and the Coastal Hubs

The shift to the maritime, Transatlantic trade began with the arrival of the Portuguese in the late 15th century, setting the stage for centuries of European competition and domination of the Gold Coast’s commerce.

The Portuguese Foundation

In 1482, the Portuguese constructed São Jorge da Mina (Elmina Castle) . Initially, the fort’s primary purpose was to secure the gold trade, which gave the region its name. However, as the European demand for labor in the New World plantations (sugar, tobacco, and later cotton) exploded in the 16th and 17th centuries, the commercial focus shifted irrevocably to human cargo. The Portuguese began trading firearms, cloth, and iron for enslaved people from the interior.

Competition and the Forts System

The immense profitability of the trade drew other European powers into a fierce competition that lasted through the 17th and 18th centuries. The Gold Coast became a military and commercial chessboard, leading to the construction of dozens of fortified trading posts along its short coastline.

-

The Dutch wrestled control of Elmina from the Portuguese in 1637 and became the dominant power for the next century.

-

The British established trading posts, most notably Cape Coast Castle, which became their administrative and commercial headquarters.

-

Other European involvement: Sweden, Denmark, Germany (Brandenburg-Prussia), and France also maintained forts, creating the highest concentration of European military architecture anywhere in Africa.

These structures, built on the shifting sands of global economic demand, transitioned from gold warehouses to grim holding pens for human lives.

III. The Castles: Dungeons, Despair, and the Door of No Return

The castles of the Gold Coast, particularly Elmina and Cape Coast, were the last terrestrial stops for millions of Africans before their forced passage across the Atlantic.

Life in the Dungeons

The experience within these dungeons was one of absolute dehumanization. Enslaved Africans, often marched hundreds of miles from the interior, were shackled and crammed into poorly ventilated, subterranean chambers beneath the European governor’s quarters. The conditions were horrific:

-

Overcrowding: Hundreds of people were often packed into spaces meant for dozens.

-

Sanitation: Lacking light, ventilation, or sanitation, the floors were perpetually soiled with human waste, leading to rampant disease and death.

-

Psychological Trauma: The enslaved could hear the daily life of the European officers above them—their music, conversation, and worship—a brutal juxtaposition of freedom and captivity.

The Door of No Return

The most poignant symbol of this era is the Door of No Return . It was through this narrow aperture that the enslaved were led, one by one, to the waiting ships. This exit marked the literal severance from their homeland, culture, identity, and family, symbolizing the final, terrifying moment before they were loaded onto ships for the Middle Passage. Once they passed through this door, their identity as Africans was systematically stripped and replaced with the status of chattel property.

IV. The Mechanics of Trade and Local Agency

The Transatlantic Slave Trade was not merely a European enterprise; it was a complex economic network that relied heavily on African political and commercial structures.

The Trade Triangle

The triangular trade route linked three continents:

-

Europe to Africa: European ships carried manufactured goods, textiles, alcohol, and, most crucially, firearms and gunpowder.

-

Africa to the Americas (The Middle Passage): These goods were exchanged for enslaved Africans, who were then transported to the plantation economies of the Caribbean, South America, and North America.

-

The Americas to Europe: Ships returned laden with raw materials produced by enslaved labor: sugar, molasses, tobacco, and cotton.

The Role of African Intermediaries

European traders generally did not venture into the interior. Instead, powerful coastal African states and groups, such as the Asante Kingdom, acted as middlemen. These intermediaries controlled the trade routes and supplied the European forts with enslaved captives acquired through two main methods:

-

Warfare: The expansionist wars of major kingdoms, often fueled by the acquisition of European firearms, were the single largest source of captives.

-

Raiding and Debt: Smaller-scale raiding and the enforcement of judicial punishment (selling debtors or criminals) also contributed significantly to the supply.

This network of collaboration, necessity, and violence ensured a steady flow of human beings to the coastal markets. The relationship was transactional: African states sought the military and luxury goods necessary to maintain their own power and prosperity, even at the cost of selling rival or subject populations.

V. The Profound Societal and Demographic Impact

The continuous extraction of prime-aged adults from the Gold Coast for over three centuries had a catastrophic and enduring impact on the region.

Demographic Disruption

Estimates suggest that millions of people were forcibly removed from West Africa during the Transatlantic trade, with a large proportion passing through the Gold Coast. This mass removal, particularly of young, productive workers, severely undermined the local capacity for agricultural development, technological advancement, and self-defense. The skewed gender ratio that resulted from the trade also caused major societal imbalances.

Political and Economic Instability

The influx of European goods, especially firearms, accelerated inter-state conflict. Wars became more frequent and devastating, changing their objective from territorial gain to the acquisition of captives for the lucrative coastal market. This arms race perpetuated a cycle of violence and instability that lasted well into the 19th century. Indigenous economies that traditionally revolved around agriculture, craftsmanship, and local trade were distorted, becoming heavily dependent on supplying the slave markets.

VI. Abolition and Transition

The height of the trade in the Gold Coast occurred during the 18th century, but by the early 19th century, abolition movements gained traction in Europe and North America.

The British Abolition Act

Great Britain, which had profited massively from the trade, passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in 1807, forbidding its subjects from participating in the trade. This was followed by the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which abolished slavery throughout most of the British Empire.

Suppressing the Remaining Trade

Following abolition, the British Navy deployed the West Africa Squadron to patrol the coast, actively intercepting slave ships. However, illegal trade continued for decades, often under the flags of other nations, forcing the British to engage diplomatically and militarily with local chiefs to cease the practice entirely. The Gold Coast transitioned into a formal British colony by the late 19th century, shifting the focus once again to commodities like gold, cocoa, and palm oil, often extracted through forced labor under colonial rule.

VII. Legacy, Memory, and the Diaspora

The legacy of the slave trade remains a vital part of Ghana’s national identity and its connection to the global African Diaspora.

Connecting the Diaspora

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the forts and castles have become sites of pilgrimage, offering a spiritual and historical connection for African descendants in the Americas and the Caribbean. Ghana has actively embraced this role, notably marking 2019 as the "Year of Return," encouraging African diasporans to visit and reconnect with their ancestral homeland.

Confronting the Past

The historical record within Ghana necessitates confronting the complex issue of African involvement. While the majority were victims, the legacy also includes the acknowledgment that powerful African political entities played a role as commercial partners. This nuanced historical perspective is essential for both healing and education.

An Enduring Symbol

Today, the castles stand not as symbols of European victory, but as UNESCO World Heritage Sites and powerful educational tools. They represent the resilience of the human spirit and serve as a powerful reminder, often etched in the stones and dungeons, that humanity must forever guard against the dehumanization and commodification of any people. Ghana’s history serves as a permanent, tangible link in the chain of memory connecting a continent with its diaspora, ensuring that the terrible journey through the Door of No Return is never forgotten.